Day 10. The Atlantic Ocean

Timezone: UTC-3.

Breakfast with a Greek Orthodox priest. We talked about theology, the Reformation, liturgy, and a few other things such as how one gets on a “Russian steamer” from Greece to America in 1947 – an experience rather different from cruising with the ship we are on.

Evening with Irish music again, which was truly splendid, and pub quizzes in between, which we are slowly getting better at. A bold plan emerges: I will have learned the lyrics to all the Irish songs played here, and we will have won at least one quiz before Sydney.

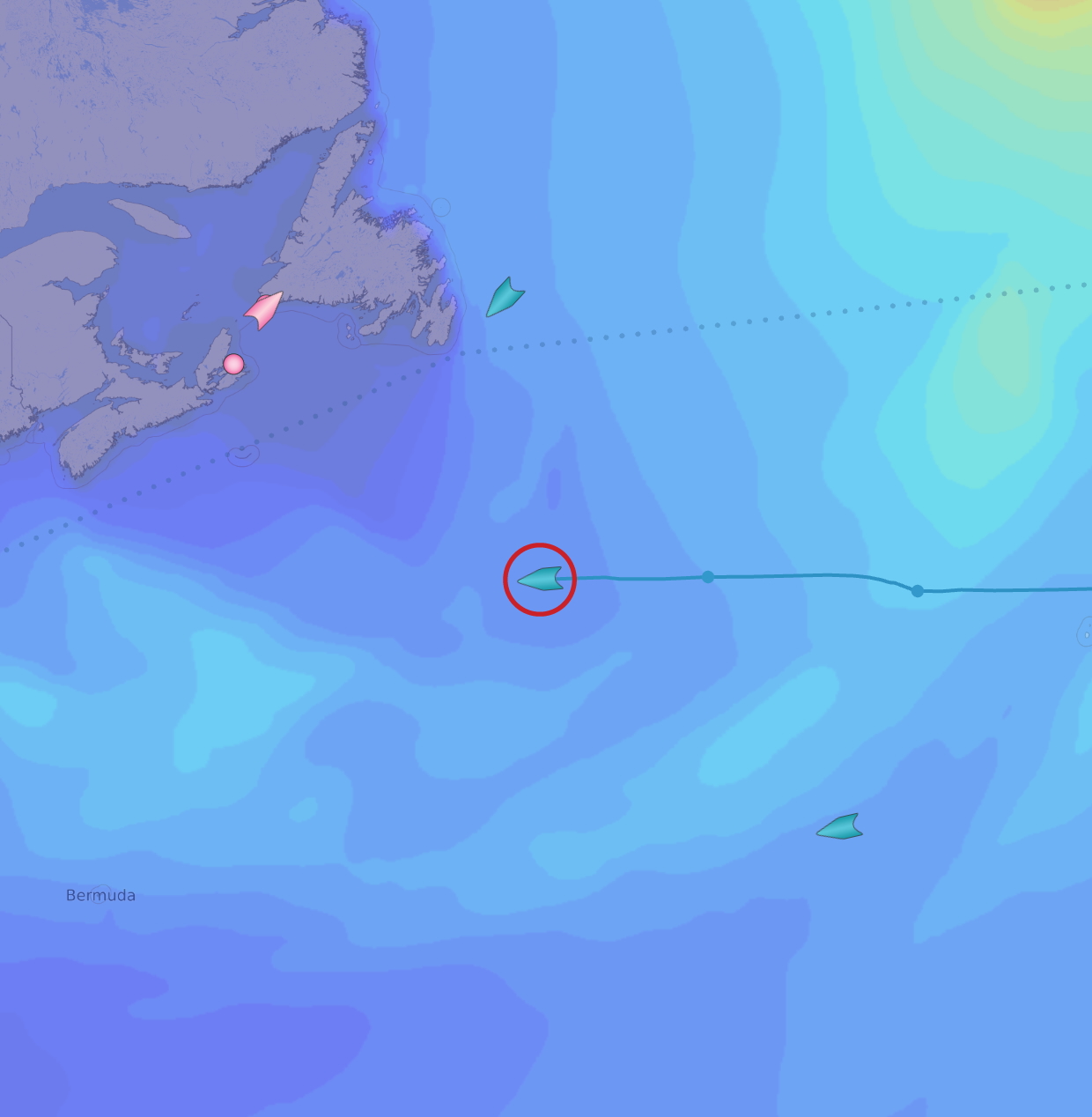

We are passing by the wreck of the “Titanic”, heading firmly towards Nova Scotia and New York. No bergs in sight, though it's not a “flat calm, like a mill pond, not a breath of wind”, either. After spending the day with, amongst others, a Greek American and the Irish, the connotation of our direction doesn't escape me. I hope they won't twist my last name at Ellis Island.

‘What do they say is the trouble?’ asked William T. Stead, a leading British spiritualist, reformer, evangelist, and editor, all rolled into one. A professional individualist, he seemed almost to have planned his arrival on deck later than the others.

‘Icebergs,’ briefly explained Frank Millet, the distinguished American painter.

‘Well,’ Stead shrugged, ‘I guess it’s nothing serious; I’m going back to my cabin to read.’

Mr and Mrs Dickinson Bishop of Dowagiac, Michigan, had the same reaction. When a deck steward assured them, ‘We have only struck a little piece of ice and passed it,’ the Bishops returned to their stateroom and undressed again. Mr Bishop picked up a book and started to read, but soon he was interrupted by a knock on the door. It was Mr Albert A. Stewart, an ebullient old gentleman who had a large interest in the Barnum and Bailey Circus: ‘Come on out and amuse yourself!’

Others had the same idea. First-class passenger Peter Daly heard one young lady tell another, ‘Oh, come and let’s see the berg – we have never seen one before.’

And in the second-class smoking-room somebody facetiously asked whether he could get some ice from the berg for his highball.

[…]

The ice soon became quite a tourist attraction. Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen, a middleaged manufacturing chemist from Toronto, used the opportunity to descend on a more distinguished compatriot, Charles M. Hays, President of the Grand Trunk Railroad. ‘Mr Hays!’ he cried, ‘Have you seen the ice?’

When Mr Hays said he hadn’t Peuchen followed through – ‘If you care to see it, I will take you up on deck and show it to you.’ And so they went all the way forward on A deck and looked down at the mild horseplay below.

Possession of the ice didn’t remain a third-class monopoly for long. As Colonel Gracie stood in the A deck foyer, he was tapped on the shoulder by Clinch Smith, a New York society figure whose experiences already included sitting at Stanford White’s table the night White was shot by Harry K. Thaw. ‘Would you like,’ asked Smith, ‘a souvenir to take back to New York?’ And he opened his hand to show a small piece of ice, flat like a pocket watch.

Walter Lord, “A Night to Remember”